Was a Plains Art Form That Continued to Flourish During the Reservation Years

Leaf Litter

Bringing Back the Buffalo

The indigenous people of the North American Plains and the buffalo on which they depended (Bison bison) were nearly brought to extinction at the hands of European settlers. Today, they are first to thrive together again.

Past Amy Nelson

Archaeological records testify that the lives of indigenous North American people take been intertwined with the buffalo (American bison: Bison bison) since their paleo-American ancestors first inhabited the continent. Tragically, they both suffered virtually extinction at the hands of European settlers. But though they were slaughtered, confined, removed from their habitat, and stripped of their very way of life, these two resilient, interconnected, and powerful North American natives survived. Cheers in large function to the efforts of Native Americans and Offset Nations, they are poised to thrive together again.

Article Alphabetize

Before the arrival of Europeans, 30-threescore million buffalo migrated through and roamed the Great Plains of North America, from the Appalachians to the Rockies and from Alaska to Northern United mexican states. For the indigenous peoples of this vast region, the significance of this large, nomadic animal cannot be overstated. The buffalo was their primary source of food, clothing, shelter, and textile goods. But it was also much more.

NPS Photograph by J Schmidt

To Native peoples of the Plains, the buffalo was a living link to their culture, spirituality, and very identity. Primal to the creation stories of cultures such as the Crow, Cree, Arapaho, Ute, and Lakota, the buffalo was—and is still today–regarded as sacred and divine. For some indigenous Plains cultures, the buffalo is blood brother; for others, the very source of human life. The Ute tradition explains that humans originated from a buffalo blood jell. In the Lakota linguistic communication, the word for buffalo is "Tatanka," which translated to "He who owns u.s.a.." According to Lakota legend, the Gift of the Sacred Pipe and the Seven Laws- items central to the spiritual manner of life-were brought by the White Buffalo Calf Woman, a immature adult female who transformed into a white buffalo dogie subsequently instructing the Lakota people in sacred ceremonies and informing them of the value of the buffalo. The spirit of the buffalo was praised before hunts, which were typically communal and sometimes involved the collaboration of different tribal communities. In many cultures, such equally the Métis, women and children helped in the chase. Ethnic hunters only killed what was needed to sustain the people, and butchering of the brute was frequently done in anniversary. No function of the animal was wasted.

Native people are said to have used more than than ane hundred parts of the buffalo. All edible meat was roasted, broiled, or stale. Hides were used to brand wearable, tipis, boats, moccasins, bedding, parflèches, and saddle covers. Bladders were made into storage bags. Bones were carved into tools and toys. Hair was woven into rope and stuffed into dolls. Even the buffalo's sinews were used, as bowstrings and thread.

The Buffalo was office of u.s., his mankind and blood existence absorbed past u.s. until it became our ain flesh and blood. Our clothing, our tipis, everything nosotros needed for life came from the buffalo's body. It was hard to say where the animals ended and the human began. -John (Fire) Lame Deer, Oglala-Lame Deer Seeker of Visions, with Richard Erdoes, 1972

The buffalo non only shaped the livelihoods of the human inhabitants of the Plains, it shaped its landscape and ecology. Merely by the way they grazed and migrated, they had a dramatic impact on the prairie ecosystem.

Bison travel while they graze, disposed toward dominant grasses while avoiding most forbs and woody species. Studies in the last two decades have shown that this increases plant multifariousness (Collins et al. 1998), allows the productivity of grasses to recover, and because information technology allows various forbs to flourish, enhances gas exchange, aboveground biomass, density and plant encompass (Fahnestock and Knapp 1993, Hartnett et al. 1996, Damhoureyeh and Hartnett 1997). Their grazing also encourages the growth of shrubs that provide habitat for nesting birds. The depressions buffalo create by wallowing in the mud or taking grit baths create habitat for amphibians and migratory birds when they are moisture, and shelter for mammals when they are dry. The buffalo essentially managed a vast, healthy mixed-grass prairie ecosystem.

Bison wallowing. NPS photograph by Jim Peaco

Every bit European settlers began moving w in the 1700s, however, they introduced diseases that made buffalo populations more vulnerable, increased grazing competition with horses, and hunted buffalo in large numbers to fuel the hide and tongue trade. Only far more devastating to buffalo than these factors was the white human being's widespread slaughter of the buffalo simply as a means to subjugate the indigenous people of the Plains, who relied on the animal completely.

Man sitting atop stack of bison hides. NPS Photo

According to the U.Due south. Fish and Wildlife Service, by 1872, an average of 5,000 buffalo were killed every twenty-four hour period. In 1867, Col. Richard Irving Dodge, a colleague of General Custer, is reported to accept said, "Kill every buffalo you can. Every buffalo expressionless is an Indian gone." In 1873, Columbus Delano, Secretarial assistant of the Interior nether President Grant, wrote in a written report "The civilization of the Indian is impossible while the buffalo remains upon the plains. I would non seriously regret the total disappearance of the buffalo from our western prairies, in its issue upon the Indians, regarding it as a means of hastening their sense of dependence upon the products of the soil and their ain labors."

In his 2007 book Buffalo Nation: American Indian Efforts to Restore the Bison, author Ken Zontek writes:

It becomes obvious to any observer that the treatment of the bison and Native Americans paralleled each other. Euro-Americans subjected both of them to slaughter, disease, a marginalized landscape, deprivation of customs, and alienation from their ways of living by concentrating them away from preferred habitat.

For Native Americans, who had been confined to reservations, forced into boarding schools, and subjected to policies that created perpetual poverty, recovery of the buffalo was near impossible. But some prevailed. Ane recovery effort worth noting is that of Samuel Walking Coyote, a Pend d'Oreille man who was married to a Salish woman and living on the Flathead Reservation in Blackfeet territory in Montana. According to the accounts of residents and traders, Walking Coyote became involved with a Blackfoot woman, which acquired a domestic dispute. Though it was eventually resolved, Walking Coyote needed to make apology with the Salish community in the Flathead Valley. To do so, he was advised to bring buffalo to them. In 1873, he and his wife captured and cared for six buffalo calves. A decade later, the herd numbered 13 and was purchased by Michel Pablo, the son of a Blackfoot adult female. Pablo let the buffalo roam gratuitous on the Flathead Reservation in the hopes they would propagate. They did. Pablo's partner, Charles Allard, procured more buffalo and the herd continued to expand. Past the turn of the century, as much equally 80% of the nation'southward buffalo possessed some claret from the Pablo-Allard herd. Just in 1904, President Roosevelt signed a bill into police force that ordered the execution of the Dawes Human activity of 1887 on the Flathead Reservation. The Human action divided tribal land into allotments and granted citizenship to tribal members who accepted the allotment and agreed to live separately from their tribe. With the opening of tribal communal land to settlement, Pablo could no longer allow his herd to roam costless. He attempted to sell the herd to the U.S. government, but the price they offered was unacceptable, and he instead sold them to Canada. In 1907, Pablo delivered 716 bison to Canada. 631 went to Buffalo National Park and 85 went to Elk Island National Park. The descendants of those bison remain in those parks today.

In 1886, Buffalo were and then shut to extinction that William Temple Hornaday, Chief Taxidermist for the Smithsonian Establishment, travelled to Montana to collect specimens to stuff and display for future generations to bask a glimpse of an extinct mammal. A yr afterward, the American Museum of Natural History mounted their ain exhibition to Montana obtain bison specimens. They found no bison. According to the U.Southward. Fish and Wildlife Service, by 1902, there were simply 700 bison left in the U.Southward. in private herds and 23 animals in a public herd at Yellowstone National Park.

In 1905 Hornaday and other conservationists frustrated over the U.Due south. government's failure to purchase Pablo's herd, founded the American Bison Society to protect and restore bison. Their efforts helped establish herds in the National Bison Range in Montana (which later donated bison to other protected areas to form more herds) and Fort Niobrara National Wildlife Refuge in Nebraska. Meanwhile, managers at Yellowstone began working to recover their buffalo population. Past 1990, their herd had increased to more than than three,000.

Just what about Native American efforts to bring the buffalo dorsum to tribal land?

The passing of the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, which ended the allocation process, restored some un-allotted land back to tribes, increased Indian cocky-government and control, and opened up some opportunity for restoration. The Crow Reservation in southeast Montana, for example, obtained bison from Yellowstone and the National Bison Range in the 1930s and began to constitute their ain herd. By the 1960s, the herd grew to over 1,000 and the Crow had expanded their rangeland to more 24,000 acres. Despite the Tribe'south efforts to incorporate the buffalo using topography and fencing, many of the animals wandered beyond the boundaries of the reservation. Around the same fourth dimension, there was a shift in federal philosophy with the implementation of the Termination Policy of the 1950s-60s, which intended to terminate the autonomy of tribes and assimilate Native Americans into Western culture. Tragically, regime and neighboring ranchers' concerns over the spread of brucellosis, a disease that causes stillbirth among cattle, led to the eradication of the Crow'due south herd. The Crow thus suffered a second slaughter of their sacred animate being.

The 1970s, still, marked the beginning of a turning point for both Native Americans and the buffalo. As a result of Native American activism and advocacy, the U.South. government passed the Indian Self-Determination and Education Help Human action of 1975, which rejuvenated tribal government. At that fourth dimension, the Crow began re-establishing their herd, and many other tribes, such as the Lakota, Shoshone-Bannock, Assiniboine, Gros Ventres, and Cheyenne established herds with buffalo from the National Bison Range and national parks.

Tribal restoration of buffalo took a powerful and promising plow in the winter of 1991, when representatives from 19 tribes in S Dakota, Montana, New Mexico, Nebraska, Wisconsin, and California gathered for a coming together hosted by the Native American Fish and Wildlife Order. The Social club had procured funding from Congress for tribal buffalo restoration, and the meeting was the beginning of the formation of the Intertribal Bison Cooperative, a pan-Indian arrangement that would unite Tribes in the endeavor "to restore buffalo to Indian Country in guild to preserve our historical, cultural, traditional, and spiritual relationship for future generations." They emphasized an intention to restore the buffalo with "wild integrity," and to not employ intensive practices such as feedlots, premature slaughter, and genetic engineering science.

Since the Intertribal Bison Cooperative'south official founding in 1992 and its subsequent reorganization in 2009 every bit the Intertribal Buffalo Council (ITBC), the system has expanded to include 63 Tribes in twenty states. Collectively they have restored more than 20,000 buffalo to tribal state. Through partnerships with national parks and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, ITBC helps match tribal requests for buffalo with surplus buffalo from parks, refuges, and preserves. The ITBC besides supports fellow member Tribes past offer an assortment of technical services, such every bit guidance on herd introductions, site visits to determine the feasibility and conduct monitoring of restoration efforts, and the development of business organization and marketing plans. For several summers, they collaborated with tribal colleges to run a program offering tribal students hands-on instruction in all facets of buffalo restoration, including Native food preservation techniques. Through a grant plan, they besides support Tribes with expenses related to infrastructure improvements, equipment, meat processing, corral and handling facilities, salaries, and more.

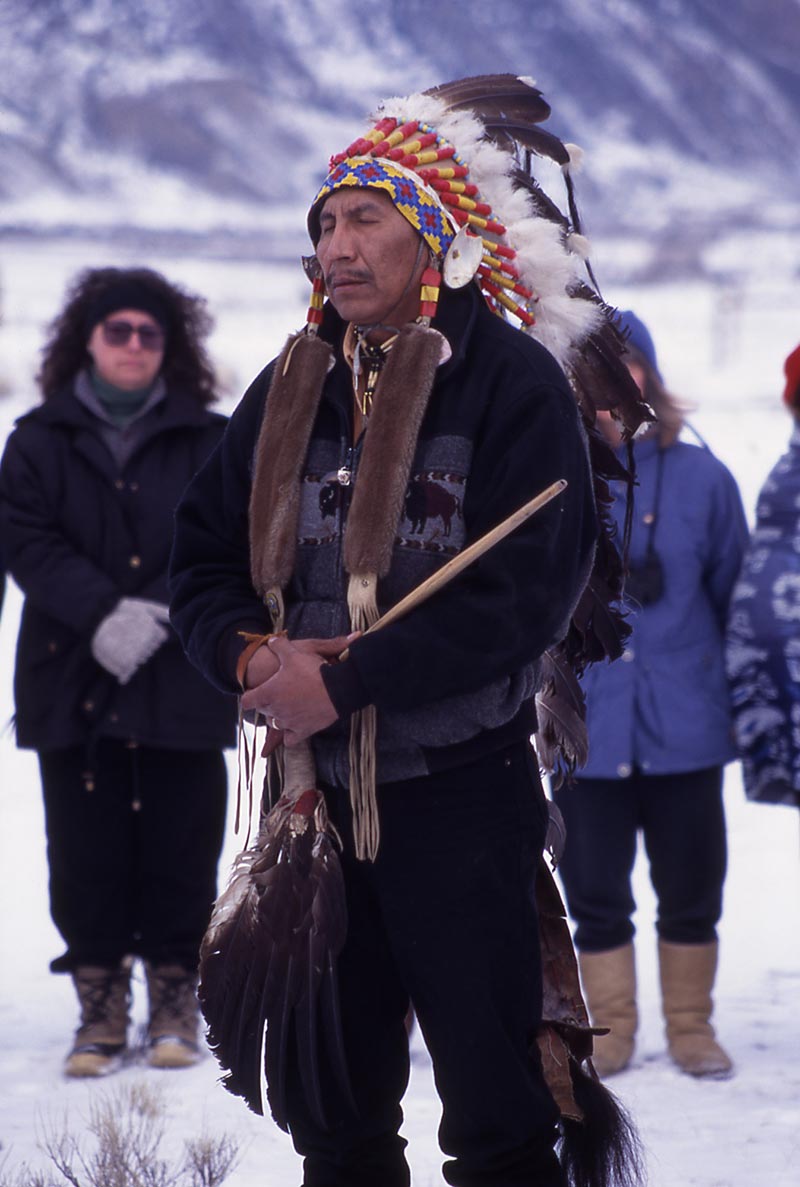

Chief Arvol Looking Horse, of the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota Nations at prayer calling for the end to the slaughtering of Yellowstone buffalo. NPS Photograph by Jim Peaco

The ITBC has too proven to be a strength in advancement. They helped lobby the federal authorities to put bison into reservation food distribution programs, and they are a vocal protestor of the slaughtering of hundreds of bison that wander beyond the boundaries of Yellowstone National Park. Though the Yellowstone herd is the largest remnant of genetically pure bison, animals that stray from the Park are still slaughtered every winter out of fear of brucellosis.

In the Jump of 2016, thanks in big part to lobbying efforts by the ITBC, President Obama signed the National Bison Legacy Human action, legislation that designates the North American bison as national mammal of the United States. Though the irony of the buffalo becoming a symbol for a nation that nearly destroyed it, the Human activity spells out, in its findings, an acknowledgement of the economic and spiritual significance of the animal to Native Americans, and a recognition of Native American'southward efforts to restore the buffalo to Tribal State.

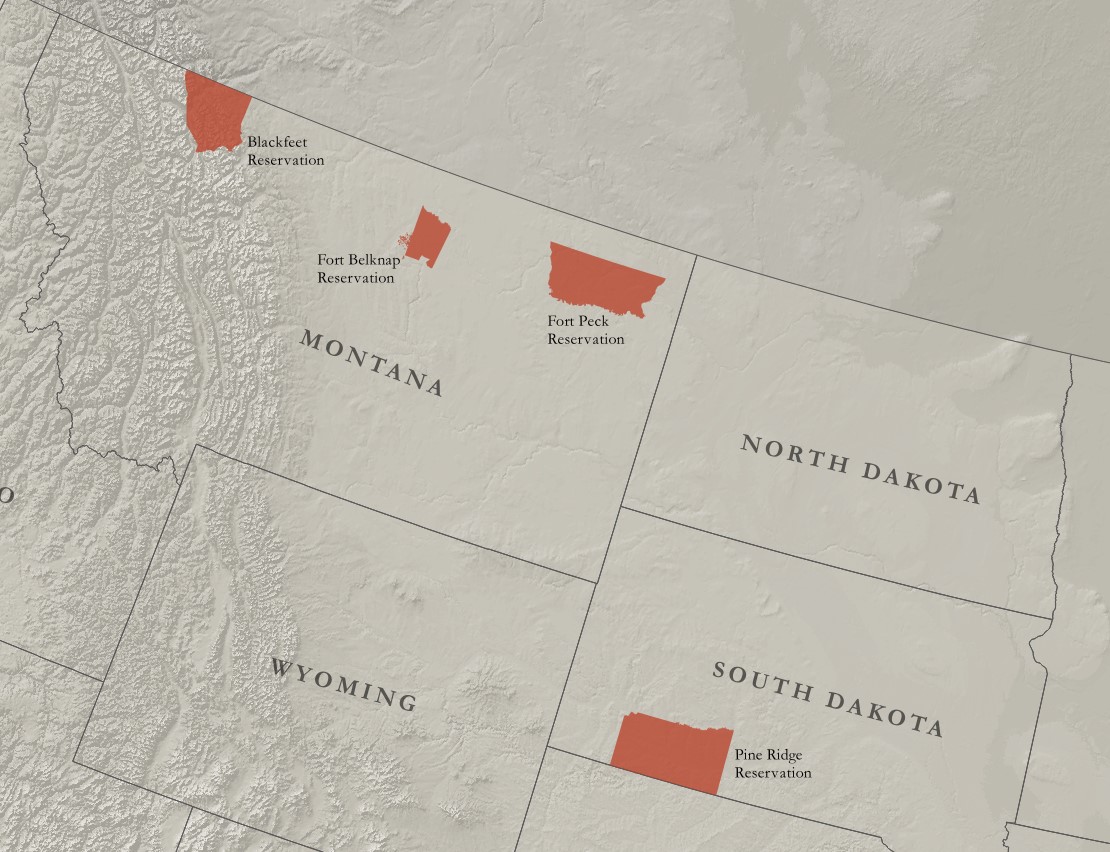

One ITBC collaborator that has proven to be a powerful and committed partner in the restoration of buffalo to tribal lands is the organisation Defenders of Wild fauna. Defenders has successfully worked with tribes on the Fort Peck and Fort Belknap reservations in Montana to transfer 200 illness-free buffalo from Yellowstone that would have otherwise been killed to tribal lands. They as well friction match funds with the Fort Belknap Reservation to buy holding to aggrandize their at present 13,000-acre reserve.

Defenders has besides helped support tribal buffalo programs and herds on the Blackfeet Reservation. Since the time when their territory spanned parts of what is now Northward and South Dakota, Montana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Canada, the Dakota and Nakoda (Assiniboine) nations have been connected to the Tatanga/Tatanka Oyate, or Buffalo People. Simply in the 1870s, the U.S. authorities confined them to the Fort Peck Reservation, where, inside a few brusk years, there were no more than buffalo. Today, the return of the buffalo to Fort Peck has brought a cultural and economic resurgence. In 2015, with funding from the World Wild animals Fund, the Ft. Peck Pté Group, an organisation with a mission to develop, enhance, and perpetuate the people's human relationship with the buffalo through education and the sharing of cultural information, surveyed tribal members to determine what they valued in buffalo restoration. Informed past those values, the tribe manages a cultural herd to feed the customs, conserve buffalo, and provide cultural connectedness, and a concern herd to generate acquirement from the auction of hunts, live animals, and meat to off-reservation interests. Each twelvemonth, the Fort Peck Turtle Mound Buffalo Ranch donates 25 buffalo to tribal programs and cultural activities that include diabetes programs, homeless shelters, Dominicus Dances, pow-wows, and funerals. The Ranch also offers managed hunts that bring in anywhere from $1,000 to $6,000 per buffalo, depending on the animal's sex and historic period. The restoration of the buffalo has also brought ecological improvements to Fort Peck.

"Since we welcomed dorsum the first Yellowstone buffalo, we've seen the ecosystem revive," said Robert Magnan, Director of the Fort Peck Tribe's Fish and Game Section, in an article on the Defenders of Wildlife web site. "Grassland birds have returned, native grasses are thriving."

The regeneration of a prairie ecosystem does not occur overnight, and it can be challenging to discover studies of the ecological impact of bison restoration. A recent study of Plant Community Responses to Bison Reintroduction within Montana's Northern Groovy Plains, even so, is encouraging. The study examined how x years of bison reintroduction and livestock removal influenced institute community dynamics in a mixed-grass prairie compared to cattle-grazed rangeland. The researcher observed that bison grazing yielded higher species richness and limerick than cattle-grazing or livestock removal treatments. The same study constitute that areas where bison had been reintroduced were lower in noxious weeds than cattle-grazed areas. Scientists are currently in the midst of a three-year written report on the bear upon of bison which were restored to The Nature Conservancy'due south (TNC) Nachusa Grasslands in Illinois in 2014. "It takes a long time to obtain measurable results in a study like this," said TNC's Jeff Walk in an commodity on the TNC web site, "but with the naked eye, you can already see that there appears to be a substantial difference in height betwixt the un-grazed plots and areas where the herd spends a lot of time." Ranchers and researchers are also looking into the potential of bison to contribute to carbon sequestration.

When buffalo are restored to Native bequeathed land and reservations, the benefits go beyond ecology and nutrient sovereignty. According to Defenders of Wild animals, one of the other benefits of returning buffalo to Indian communities is the opportunity they provide for young people to learn near the erstwhile ways, and for the resurrection of the language. This is indeed happening at the Yard-12 Middle Butte Schoolhouse on the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana. When the school practical for and received a federal 21st Century Community Learning Grant to implement robotics, language, and cultural programming, one of the initiatives they launched was an annual buffalo "hunt," where students travel to a ten,000-acre ranch that serves as winter pasture for the tribal herd. The herd, which received a contempo heave of 88 buffalo calves in 2016 from Canada'southward Elk Island National Park—descendants of the herd started in 1873 by Samuel Walking Coyote and sold to Canada by Michel Pablo–now includes more than 625 animals.

Sheldon Carlson, middle, talks to the Heart Butte students about how to begin field dressing the bison. ©Tom Bauer/Missoulian

Though the Heart Butte School students do not participate in the killing of the animate being (that is done by the Tribe'due south bison managing director), they set for and participate in a traditional smudging ceremony to award the buffalo, and they help skin, make clean, and butcher the animal in the traditional way. They learn well-nigh buffalo meat, and are offered the opportunity to taste it raw. They learn about the many means their ancestors used buffalo, and how essential the animal was to the survival of their people. In the process of this "chase," the students likely begin to forge their own connection to the buffalo, one Tribal elders hope volition grow.

Chelsea Bullshoe, 13, pauses where a prayer cloth was tied on a tree at the start of the hunt. The textile was smudged and passed around the group to offering prayers before being left there. ©Tom Bauer/Missoulian

The restoration of buffalo to tribal state at Fort Belknap and the Blackfeet Reservation are merely two examples of the benefits reaped by restoring buffalo to tribal land. The Oglala Lakota people on the Pine Ridge reservation demonstrate another compelling case. Over the last several decades, the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota has come to be associated with extreme poverty, joblessness, and a suicide rate that is four times the national boilerplate. The 2.1 million acre Reservation is far removed from the state's economical lifelines, and is known as the poorest county in the United States. Life expectancy on the Pino Ridge Reservation is 1 of the lowest in the Western Hemisphere. In 2016, unemployment was nearly 90% and the boilerplate per capita income is under $9,000. But the Oglala Lakota people are known for their resilience, and they are currently pursuing a new vision for their community-ane in which they thrive in a life as intertwined with the buffalo every bit it in one case was. They founded their own community evolution corporation, which is creating a regenerative community that includes sustainable, affordable housing that is congenital past an employee-owned tribal construction company, workforce training, youth programs, powwow grounds, and a cultural heart. In the midst of this resurgence, and cheers to innovative thinking by the Oglala-Lakota people, their vision of a "modernistic, buffalo-based economy" is also coming to life.

In 2006, Karlene Hunter and Marking Tilsen, Oglala-Lakota Tribe members who had a vision to bring traditional good for you lifestyle into the 21st century, founded Native American Natural Foods, a company that creates buffalo-based nutrient products that, according to the company's web site, "promote a Native American way of wellness that feeds mind, trunk, and spirit." Longtime business concern partners in Lakota Limited, Inc., a direct marketing and customer care management company, Hunter and Tilsen had spent decades trying to amend the livelihoods of people on the Pine Ridge Reservation. When they heard, at local chamber of commerce meetings, the challenges faced by local buffalo producers in accessing money, land, and new markets, they took action and started Native American Natural Foods. Their products, all-natural, depression-calorie, jerky-like foods chosen Tanka Bars, Tanka Sticks, and Tanka Bites, are made from buffalo (much of which is prairie-raised, grass-fed, and from the reservation) and various blends of fruit, peppers, and spices. The recipes are based on and inspired by the traditional food "wasna," a mixture of buffalo meat and fruit and was considered sacred. The first Native reservation company to create a national brand, Native American Natural Foods at present sells Tanka products in major, mainstream outlets such as REI, Costco and Whole Foods.

In 2006, Karlene Hunter and Marking Tilsen, Oglala-Lakota Tribe members who had a vision to bring traditional good for you lifestyle into the 21st century, founded Native American Natural Foods, a company that creates buffalo-based nutrient products that, according to the company's web site, "promote a Native American way of wellness that feeds mind, trunk, and spirit." Longtime business concern partners in Lakota Limited, Inc., a direct marketing and customer care management company, Hunter and Tilsen had spent decades trying to amend the livelihoods of people on the Pine Ridge Reservation. When they heard, at local chamber of commerce meetings, the challenges faced by local buffalo producers in accessing money, land, and new markets, they took action and started Native American Natural Foods. Their products, all-natural, depression-calorie, jerky-like foods chosen Tanka Bars, Tanka Sticks, and Tanka Bites, are made from buffalo (much of which is prairie-raised, grass-fed, and from the reservation) and various blends of fruit, peppers, and spices. The recipes are based on and inspired by the traditional food "wasna," a mixture of buffalo meat and fruit and was considered sacred. The first Native reservation company to create a national brand, Native American Natural Foods at present sells Tanka products in major, mainstream outlets such as REI, Costco and Whole Foods.

"Our vision," says Tilsen on the company's web site, "is to build our Tanka make so strong that we can have a positive impact on the number of buffalo, the health and economic system of our people, and the environment of the Great Plains." By continuing to run a successful company that employs and empowers tribal members on the Reservation, and past partnering with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation, to create the Tanka Fund, a charitable fund to support programs that return buffalo to the Great Plains, they are clearly on the way to realizing that vision.

The cultural, health, and economic benefits of buffalo on the Pine Ridge Reservation are also getting a boost from 1 Spirit, a Native arrangement with a mission to help the Lakota encounter their basic needs and provide a culturally rich life for their youth. One Spirit and the Oglala Lakota are in the final stages of building their own buffalo processing facility. Called "Tatanka Watakpe," which means "charging buffalo," the facility will enable local hunters, livestock managers, and ranchers to process their meat on the reservation, without having to travel an hour to the nearest processing facility and pay someone else to do it. Information technology will also provide jobs and allow the Oglala-Lakota to butcher meat according to traditional practices.

Like the buffalo itself, the efforts of indigenous peoples' efforts to restore the buffalo to tribal lands are not limited past national or political boundaries. In 2014, Plains tribes from Canada and the U.S. gathered in Blackfeet territory in Browning, Montana to sign the Northern Tribes Buffalo Treaty. The Treaty established intertribal alliances for the restoration of bison on reserves or co-managed lands inside the U.South. and Canada. In collaborating to restore the buffalo, signatories aim to re-affirm and strengthen cultural ties, conserve and restore native grassland, encourage youth education, and improve health and economic system. Commodity number ane of the Treaty is "Conservation." It reads:

Recognizing BUFFALO as a practitioner of conservation, We, collectively, hold to: perpetuate conservation by respecting the interrelationships between the states and 'all our relations' including animals, plants, and female parent globe; to perpetuate and proceed our spiritual ceremonies, sacred societies, sacred languages, and sacred bundles to perpetuate and practice every bit a ways to embody the thoughts and beliefs of ecological balance.

At that place are at present hundreds of thousands of buffalo in Northward America. The precise number is unclear, since some entities approximate merely pure-bred bison (vs. those that accept been cross bred with cattle), and some just include wild bison. What is clear is that Native people have played a tremendous role in buffalo recovery. The "Buffalo People" and the indigenous people of the Plains are once once more intertwined—this fourth dimension in a long-overdue, but epic comeback.

Sign up for Leaf Litter

Scan by topic

Browse by yr

Source: https://www.biohabitats.com/newsletter/ecology-culture-and-economy-lessons-from-indigenous-traditions-and-innovation/bringing-back-the-buffalo/

Post a Comment for "Was a Plains Art Form That Continued to Flourish During the Reservation Years"